Dear Friends,

My book, Tarot for Change: Using the Cards for Self-Care, Acceptance and Growth came out this week! Check it out if you want to. It’s available in the US, UK, and there’s an e-book and audio version at the US link, through Penguin Random House.

In other news, I’m excited to be doing audio versions of the offerings again. There’s a link below the image of the cards below, to listen if you prefer.

I’m running on fumes after a very busy few weeks, so that’s all for now. Hope you enjoy the offering this month.

Thank you all so much.

Jessica

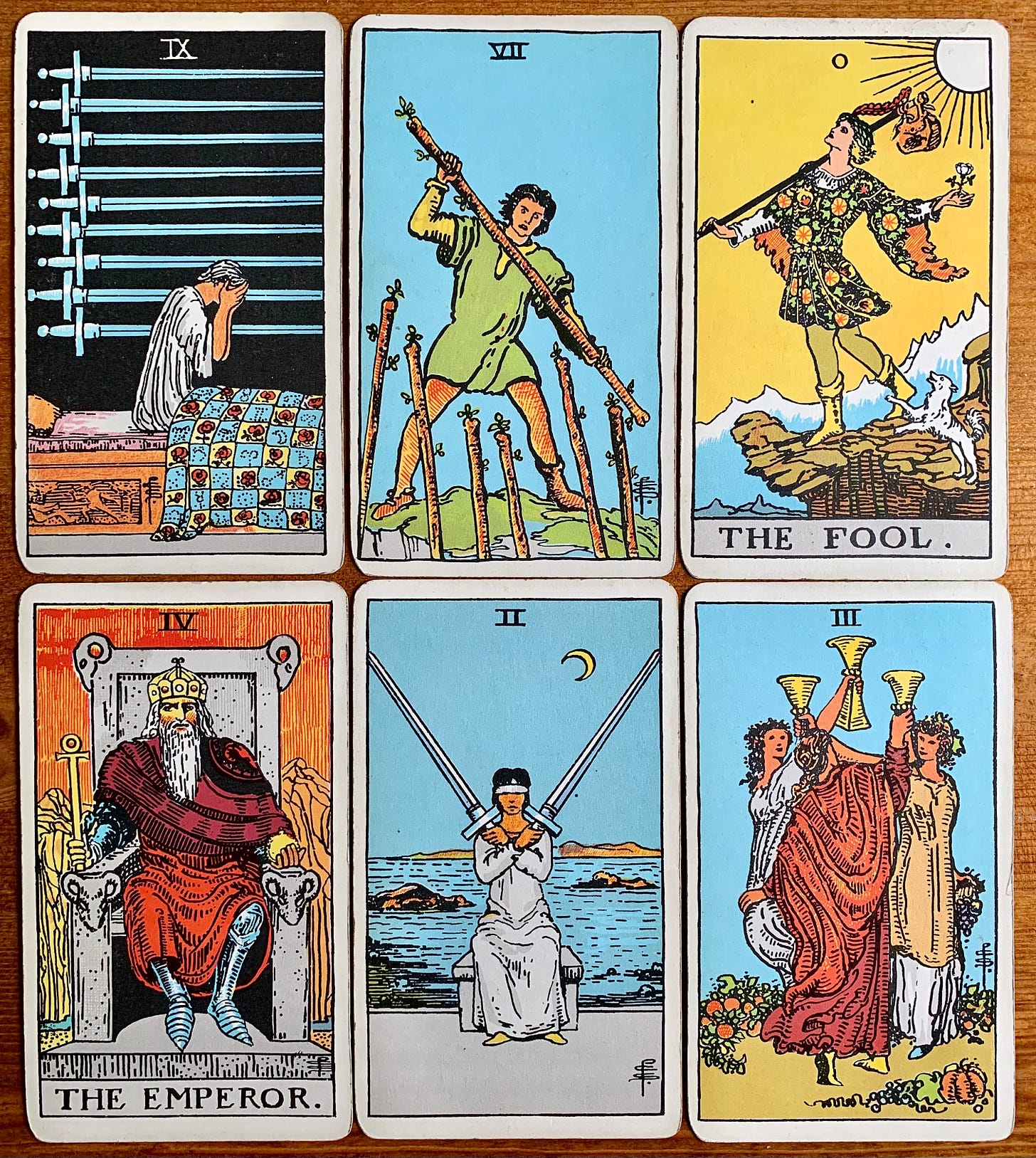

[Image description: Six Tarot cards by Pamela Colman Smith from the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot. Left to right and top to bottom, they are Nine of Swords, Seven of Wands, The Fool, The Emperor, Two of Swords and Three of Cups.]

To listen to me read this offering aloud, click here.

I re-encountered a helpful thing in the Mind & Emotions book this week, at a time when I really needed it, the week my book is out. As is often the case in clinical psychology books, the helpful thing has a sort of tragically unpoetic name—the validity quotient. But it’s essentially “a measure that gives you an idea of how accurate thoughts are at fortune-telling.”

To find the validity quotient, McKay and colleagues write, you can ask yourself the following questions, which they’ve drawn from the work of Erica Moses and David Barlow:

“How many times have you made this prediction in the past five years?

How many times in the past five years has it come true?”

And then to calculate the accuracy of your predictions, you divide the number that came true by the total number made.

They even make a solid case for making a “predictions log,” which even if you don’t see yourself ever doing, just knowing it’s a thing could be useful. The concept is that whenever you find yourself really worrying hard about something, expecting the worst (Nine of Swords), you write it down. To log what you’re worried will happen, and when.

And then as time goes on, you’ll check back and see how the predictions have aged. How many of the logged worries came to be? You might even make a column where you can write down what actually happened, if that helps.

Doing this, according to the authors, can help people take their worries less seriously. Because you might see that the predictions are happening all the time and that there’s no real correlation with the thoughts and the reality.

And not to say thoughts aren’t real—if you’ve ever dealt with intrusive or obsessive ones I don’t have to tell you how real they can be—but if the most troublesome among them aren’t syncing up with the material experience, I think that’s a good thing to know.

I shared this idea on Twitter earlier this week, and many people replied that actually, their negative predictions are often accurate. I feel like that’s an important thing to name here, too. It’s valid. And if that’s the case, this idea might not be the most useful for you.

It feels like it would be counterproductive to make a log that affirms the link between negative predictions and negative outcomes. It seems that would likely have the effect of fortifying one’s bond with the thoughts, rather than loosening it.

I will say that—while I don’t feel I’m in a position to make any absolute statements here—I know that for me personally, the expectation of a negative outcome might cause me to miss incoming information about positive ones. My own mind has a tendency to fixate on certain things, which does make it hard to see and experience others that might not line up with what I’m planning to see.

Notably, McKay and colleagues write that negative predictions about the future serve a specific function, as many behaviors do. They write, “These thoughts are all trying to do one thing: reduce uncertainty. They seek to prepare you for bad things that might happen and somehow keep you safe.”

But, the authors ask, has it worked? Does anticipating bad things actually make you feel more secure, more prepared for bad things that may come? Or, “are you simply more scared?” (Seven of Wands)

My follow up to things like this is always, okay, yes, most times it doesn't work, or it only makes me more scared. But how do I stop doing it?

I think it stands to reason that if worry is the coping strategy—the way of dealing with uncertainty—and you find that it isn't a sound tactic because it’s a.) not actually preparing you for what’s to come and b.) not making you any more prepared for hard things when they do happen, then it’s time to find a better way.

—

On my own time I’ve been writing about The Fool this week. More specifically I’ve been writing on liminality, a word I’ve used to describe The Fool many times, but which I have a hard time articulating the meaning of.

When someone asked me to describe liminality in an interview recently, and I froze, I took that as an invitation to sit down and flesh it out. Maybe a strange thing to do with a word that is itself so related to ambiguity, but finding clarity through writing has been one of my own strategies for managing uncertainty.

In their book, Toward Psychologies of Liberation, psychologists Mary Watkins and Helene Shulman have a whole section about liminality that uses very clear, but not overly clinical or academic language. They talk specifically about what happens when something disruptive has ocurred that careens a person or people into uncertain, liminal spaces, and the different ways we tend to make meaning in such times.

One way people often deal with liminality, they write, is to renormalize—that is, find a way to return to status quo (The Emperor) as soon as possible and with as little of the incoming marginal information integrated into the center as one can get away with. This is obviously not ideal; it means we aren’t willing to change our minds to accommodate new details as they become available.

I think about how, in many spiritual traditions, adherents are taught to be kind to strangers—or Fool-like characters—for they could be Gods in disguise. Renormalization is just the opposite. Hostile where one could be hospitable, when we renormalize we double down in the old way rather than spread our arms toward what’s emerged from the horizon and wants to come in. The hardening of an existing structure to find stability in the face of the new makes a lot of sense, but it can make change more difficult in the long run.

So Watkins and Shulman pose two important questions here: “How do we learn to change the sedimented ways we understand the world, and how do we evolve new and more creative responses,” especially when the unexpected happens, and everything is gray. And I think that The Fool responds to these questions.

The Fool has been described as having no name or identity, no future or past. They relate to reality as the nomad relates to place; in full participation, tasting local berries, making medicines with the plants, bathing in the cool waters. Because the landscape of reality is always changing, The Fool keeps an eye toward the emergent. When the time comes to leave, they know it, and they go.

The Fool is best understood in relation to what they are not; the dominant structure and how they clash with the status quo. As Daniel Deardorff has written of the liminal, “it isn’t nice, it doesn’t fit, it shouldn’t be allowed, and it doesn’t belong.”

A disruption to the norm can stimulate excessive worry or negative forecasting, but it can also be an opening that offers up entire new worlds and possibilities. If the latter is not how you’re used to seeing things, it’ll take some practice. If life’s been hard and you’ve no reason to expect good things, you’ll also need compassion and grace.

The Fool holds major secrets, not minor ones. It could be a life’s work. It could also be very much worth doing. Rather than constantly “defending against dislocation and liminality,” Watkins and Shulman write that we can learn to “bear and contain the ambiguities, fears, uncertainty and uncanniness of a pilgrimage.”

I think the hard truth is that if we want change, we have to endure uncertainty. It’s a tall order for creatures with brains like ours that’s easy to say and harder to do. But having all of human history behind us also means that this isn’t a new dilemma by any stretch. Watkins and Shulman’s words on what to expect in ambiguous, liminal times, are like a charm:

“There may be a long period when contradictory ideas contend for space and adherence (Two of Swords). Supportive and witnessing relationships will be crucial (Three of Cups)…At this point, the possibility to try out new narratives, to reframe one’s story, becomes critical.”

They write that here, we “anticipate heterogeneity rather than accord.” Which means learning to make space for the thousand cascading truths, stretching our minds to hold them all in right time, and being light in the feet so we can circulate, flit from one to the next, as needed. I don’t believe that the Fool’s aim is to usurp anyone, but rather to sit with a while, break bread, swap stories. And to leave the place changed from what it was, before they came.

One of the difficulties of such a time, write Watkins and Shulman, will be “the process of discernment: how much to hold and how much to give up.” When old ways are no longer taken for granted, there is an ambiguity, where “all narratives form tentatively around an unconscious gap, a limitation of language and current understandings, an opening where the future must enter to shatter complacent expectations.”

Indeed if nothing else is sure, times of change present us with a clear task: Figure out what to take with you, and what to leave behind. It’s hard. For sure. With this, I always remember my friend and mentor Charlie running a therapy group full of people exclaiming variations of the phrase, “ugh! But it’s hard!” His response was, “Yeah it’s hard. And hard is often very much worth your while.”

—

If the predictive, convincing, fortune-telling mind is a product of our inability to “trust the process,” then The Fool is a contrasting energy, nothing if not processual.

Neither here nor there, they stand for a truth that all is relation, life is constant interaction between the organism and the environment, all with wants, needs, strengths and vulnerabilities that are ever-changing, too.

The Fool’s is an essential standpoint for anyone hoping to cultivate greater psychological agility, and the capacity to be responsive to new information in the face of hardened truths. None of us are going to just arrive somewhere one day and stay there. The body will change if the mind and heart don’t. But they will too, whether we accept it or not.

With practice we can hopefully learn to have what Ivone Gebara calls “respect for new moments,” and as Watkins and Shulman write, can “work to imagine identity less as product and more as process, a practice marked by its gestures toward otherness in oneself and others.” May we all work toward greater kindness to the strange.

You’re reading the free monthly offering. There is an option to receive these offerings weekly, as well, for $5 per month or $50 per year. If you’re interested, click here.

Either way, thank you so much for being here and we’ll see you next time.

Sources

Mind and emotions: A universal protocol for emotional disorders by Matthew McKay, Patricia Zurita Ona and Patrick Fanning

Toward psychologies of liberation: Critical theory and practice in psychology and the human sciences by Mary Watkins and Helene Shulman

Longing for running water: Ecofeminism and liberation by Ivone Gebara (quote via Watkins & Shulman)