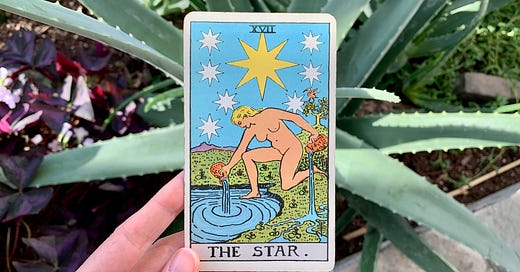

Image description: A hand is holding a Tarot card by Pamela Colman Smith in front of a large succulent. The card is The Star, which depicts a person kneeling by a pool of water under a starry sky with one knee on land and one foot in water. They are naked, holding two vessels and pouring water into both the earth and water. The card has the number seventeen in roman numerals up top, and reads “The Star” at the bottom.

To listen to me read this Offering aloud, click here.

I’ve been writing a lot this season on uncertainty and insecurity and on the simple prayers “I don’t know,” and “I will stay with you.” I’ve been turning to some of the first books that showed me how a book could get you out from a stuck or bad place. I’m re-reading Pema Chödrön’s When Things Fall Apart, and a manual for therapists called The Art and Science of Valuing in Psychotherapy by Joanne Dahl, Jennifer Plumb, Ian Stewart, and Tobias Lundgren.

I’ve always liked the sort of straightforward, matter-of-fact way that behavioral therapies approach human experience. The books I came up reading on acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) describe the interactions between thoughts, feelings and behavior in such a simple, almost mechanical fashion. I’ve felt lost many times over the years, and have found this style quite soothing.

As a spiritual person, an ACT manual leaves a lot to be desired in a few key ways but in times when I’m most afraid and trying to discern my next move, and it becomes clear—in the unique way that it so often does—that I’m not getting through without some shapeshifting, I’m always glad to have an ACT book with me. ACT is all about change, and willingness, and getting unstuck. So if I need to be a stone flying through the air to cross a river, or a salmon gliding through the sea, ACT tells me something about how.

When I really don’t know, I’ve learned there’s a practical way to embody the prayer “I will stay with you,” which is coming back to my values. In ACT, values are often described using the metaphor of a compass. When I was reading Tarot more regularly I would often draw on the notion of values as a navigation device in my interpretations of the seventeenth major arcanum; while the phrase “values work” is a dry way of describing something so rich and magical, it becomes soluble through Pamela Colman Smith’s genius rendering of The Star.

Dahl and colleagues describe values work as being to do with expanding the opportunities that are available for us to move in ways that are truly vital. They believe we can expand the potential for nourishment and intrinsic rewards that come with our behavioral choices, and minimize the amount of time we spend doing things because we feel like we should, are afraid to feel certain things, or for whatever other reason.

A couple years ago I read this remarkable interview with philosopher Brian Massumi who was talking about something similar, I think. He said that uncertainty is empowering because it offers a “margin of maneuverability,” and if we could learn to shift our awareness to the potential inside that margin rather than only “projecting success or failure” into the future, we could access Massumi’s notion of hope, a quality that’s also often linked with The Star.

For Massumi, hope involves the “next experimental step” not some fantasy of a distant time. Focusing on the next experimental step is neither settling for less nor going for more, he says, rather “it’s more like being right where you are — more intensely.”

So this is another way to talk about values work; it’s about locating and broadening your margin for immanent choices that are gratifying, full of life, and possibility. It is about learning how to spend more time in the spaces that you’ve been too afraid to be in, or to little-by-little hone the skills you need to go places you wouldn’t have dared go, before. Put this way it’s an exciting prospect, really. And in some ways it’s actually made possible by uncertainty, because if you were sure about things, you wouldn’t be doing this work to begin with.

Importantly, Dahl and colleagues differentiate values from goals. While goals involve a degree of certainty around where you’re heading and what it will take to get there, values are a bit more vague with a lot of blanks to fill in. A value might be something like honesty, solidarity, faith, care, commitment, or creativity.

Values are not stories—they don’t have a beginning, middle or end—which I think is what makes them so useful in times that lack substantial or clear meaning. Instead they’re a way to draw out themes, based on what’s most precious and meaningful. Values ask questions. They invite you to articulate what matters most, what you truly want your life to look like, and what sorts of artifacts, poems and maps you might like to leave behind.

There are obstacles to this work, of course. One, write Dahl and colleagues, is that we’re verbal creatures whose minds latch onto things that confuse our sense of true north. We are quick to go astray, become lost easily, and often find ourselves deep in the woods with a weird trick compass whose arrow fluctuates wildly. (The following obstacles are also drawn from Dahl and colleagues’ The Art and Science of Valuing in Psychotherapy.)

Another obstacle is that the needs and wants which are most true for us and linked with our core values are sometimes punished or ridiculed when we’re young. So as adults, we might be afraid to want or need the things we do because we feel guilty or ashamed. Further, if you live in an environment that aggressively stimulates artificial desires for the sake of economic growth, it’s no accident when you're running all over trying to get things that don’t do for you what they said they would.

And then a lot of us fixate on outcome over process at least in part because we’re brought up in educational systems that emphasize at times arbitrary standards of achievement rather than cultivating interest in the art of learning. From a young age, our attention is diverted from what’s intrinsically rewarding—like curiosity, awe, and meaning-making—toward behaviors that are extrinsically or institutionally rewarded. This results in an orientation that often needs some interrogating later on, so that we can learn to love a process just as much if not more than we love a finished product.

Our self-worth, too, gets tied in early with qualities that have little to do with core values. Tons of us believe that if we looked a certain way or had a certain amount of money we’d be happy, only to find out once we’ve caught the carrot—if we’re ever lucky enough to do so—that it’s just a chunk of hollowed out aluminum, spray painted orange. You don’t really need that carrot, so it will never be enough.

Obstacles to contacting true values are plenty but Dahl and colleagues believe that we can learn to maneuver around them once we see them. We don’t have to be rich, powerful, or beautiful, or even have access to a wise woman in the woods to get un-lost. With a bit of spit and willingness, we can shine and restore a foggy trick compass into one that functions well and points toward a rich and vital path.

Here’s what they say we should do:

First, we should identify our values in a number of life domains, like leisure, intimate relationships, community and spirituality. Then take some time to consider what the authors call “reinforcing qualities,” in each. I’ll give an example:

I value being supportive, and that value spans across multiple domains including my vocations, intimate relationships, and community. What reinforces me in doing supportive behaviors is the intrinsic reward of feeling connected with others, and a part of something greater than myself.

There are other things that reinforce supportive behaviors too that are less sustainable. For instance, sometimes I do supportive things because I want to feel valued or because I want to avoid feelings of guilt or helplessness. Those kinds of reinforcers are not ultimately what sustains my ability to be supportive because they can lead to compulsive caregiving, overextending, resentment and exhaustion which in the long run diminish my capacity to live in alignment with the value.

So once you’ve determined some of your values and what reinforces you to move in alignment with them in various domains of your life, you can start to look into how aligned your behaviors are with your values in reality.

Though I value being supportive across domains, I’m not always supportive. Sometimes painful feelings get in the way, like when someone I’m close to has wants or needs that conflict with my own. Sometimes I make myself too busy to be there for people I care about, or become overwhelmed by difficult situations because I haven’t set proper boundaries. So here, I’m noticing where I stop myself from moving into the margin of values-aligned behavior, and starting to wonder about how I might be more willing to go there, more often. Maybe I need to lean into rest, or set better boundaries.

The authors suggest taking a sort of behavioral inventory to help identify the function of common daily behaviors. List things you do often, and then place them into one of four categories based on four possible functions the behaviors might serve:

1.) Avoidance (the behavior helps you avoid feeling lonely or anxious);

2.) Short-term positive reinforcement (or getting a “quick fix”);

3. ) Pliance (or doing something because you think you should); and

4.) Intrinsic positive reinforcement, which is “associated with a sense of vitality from living in accordance with a value” (2009).

Of course, behaviors can serve more than one function.

Taking time to consider the function of common behaviors can give us a better sense of what tends to drive our choices and help us make space to reconsider our motivations if necessary. Maybe a lot of things you do during the day are motivated by avoiding certain feelings—like compulsively checking social media to avoid feeling lonely—or by instant gratification. Or maybe a lot of what you do every day is intrinsically rewarding in which case, right on.

You might notice that much of what you do is related to keeping your body alive; a lot of people who read this newsletter live in America, where people don’t have equal or adequate access to housing, healthcare, or nutritious food and are therefore forced to spend a lot of time working to survive.

The authors of the book acknowledge that while some common daily behaviors are not intrinsically rewarding, that doesn’t make them wrong. They might still be means to valued ends—like having a place to live or health insurance—that ideally create a broader margin to maneuver in valued ways, but don’t always.

If you do find that most of your day is spent doing things that serve a function other than that they’re intrinsically rewarding, take the time to consider the ways capitalism as a socioeconomic environment is hostile to values-aligned living.

Once you’ve taken stock of what you do and why you do it, you can get to work on dreaming. To me, this is the fun part. What goals could you experiment with that would broaden the margins of what’s possible? When you aren’t doing things to avoid discomfort or because you feel like you should but because of the things that you value truly, what will you be seen doing?

Choose goals and pursue them. And, Dahl and colleagues assert the importance of pausing to evaluate what we’re doing so we can course correct when necessary. And it will be necessary. Because values are often conditioned or tainted by social contexts or rigid ideas that we have about ourselves, it’s crucial to “experiment with many moves and gather experience in order to be able to discriminate between vital and nonvital,” they write (2009).

Someone recently retweeted a daily Tarot card I’d posted on February 19, 2021 that included a quote from James Hillman which said “the plan is the sensitivity.” It was paired with a sailing metaphor Hillman had used to describe the idea that in life we’re never actually on course, we’re only ever correcting. He warned against a life spent striving for goals that function more as “guiding fictions,” and uplifted sensitivity to the present moment as a protective charm against that.

I think this is what Dahl and colleagues are saying about values work, and also what Massumi was getting at. We’re always correcting; it’s normal, and does not indicate failure. To borrow from Massumi and Hillman, hope lives in our ability to focus on the “next experimental step,” and sensitivity is a solid plan.

I hope this is supportive for you as you dream your new year. <3

To listen to me read this Offering aloud, click here.

You’re reading the free monthly Offering for January 2023. I make Offerings weekly—in both text and audio format—for those interested in supporting with a contribution of $5 a month or $50 a year. If you’d like to sign up to receive the free monthlies or upgrade your subscription to receive the weeklies, hit the subscribe button below.

Either way, thank you so much for being here.

Sources

Dahl, J., Plumb, J., Stewart, I. & Lundgren, T. (2009). The art and science of valuing in psychotherapy: Helping clients discover, explore, and commit to valued action using acceptance and commitment therapy. New Harbinger.

Thank you - this is the first post of 2023 and it was a sorely needed read. Really appreciate your work, and your words.

The next experimental step - I can work with that 😊