Dear Friends,

I realized I’ve skipped out on these little pre-offering notes these last several months. I’ve never been one for pre-depth plunging small talk but I do like a quick check in and also want to say happy new year to everyone, and also thank you.

I’d be giving my own drive to read and write more credit than is due, were I to say that without you these writings would probably just be private journal entries. More truthfully, without you I wouldn’t be doing them. Not like this, at least. I doubt I’d be asking a fraction of the questions I am without you being here, with me, wanting to know too.

I’ve been working hard to calm down since Tarot for Change came out (if you haven’t grabbed a copy you can do so here) but am eager to offer some classes again this winter and will announce those here as soon as I’ve got the dates picked out.

This past summer I started making weekly offerings for people who are interested in supporting my research and writing with a contribution of $5/month or $50/year. At this point there’s a small book’s worth of writings in the archives—on psychology, mythology and folklore, theology, ecology, and things of that sort—all which you get access to when you sign up.

I hope you enjoy the offering this month. It’s a bit of a whopper at almost 3000 words, but a real labor of love that I’m grateful to put out in the world on this new year’s day.

Onward,

Jessica

To listen to me read this offering aloud, click here.

On New Year’s Eve I pulled the Eight of Cups for myself and remembered something I’d read and written about last year in Marie-Louise von Franz’ book The Interpretation of Fairytales. It’s not really related to the rest of this offering, but I wanted to share it anyway because it’s an image I come back to again and again, and I think relevant to the ending of a year and the energy of letting go.

Sometimes in fairytales when a hero’s been questing, and they’re either fleeing with a treasure they’d managed to grab, or escaping some other danger, they start tossing out their valuables as they run. They’re going along, sometimes shapeshifting, and throwing out combs and handkerchiefs and other such things. It’s a fact of life that the things we carry are prone to shifting from aid to liability, and a skill to know when something’s ready to be relinquished.

Even though the objects may have deep sentimental or even worldly value, like how the person in Pamela Colman Smith’s Eight of Cups is abandoning a fat pile of gilded objects that are probably worth a fortune, somewhere along the way they start to do more harm than good and if you’ve ever been in this situation, you know well the feeling that it's either them or you.

But sometimes, in the stories, something amazing happens when the valuables get thrown out; a comb becomes a forest that a villain gets swallowed up in, a handkerchief turns to flames that engulf whole valleys so that there’s no way through to the fleeing hero. I like to imagine that the things I let go of become part of a supportive, magical chorus that ultimately helps me along.

Marie-Louise von Franz says that while tossing valuables is often read as the product of a hero being panicked or chaotic, discarding valuables in an escape is actually a powerful offensive strategy. Clinging is a defensive posture, it makes the body and spirit stuff. And as a body worker might tell you, when a muscle is stiff it is less strong. Sloughing off surplus, on the other hand, is liberatory. It creates mobility.

Von Franz writes, “There are situations where one absolutely has to give up wanting anything, and in this way one slips out from under; one is not there any longer, so nothing more can go wrong. When one is confronted by a hopelessly wrong situation, one must make a drastic leap to the bottom of open-minded simplicity, and from there one can live through it” (1996).

—

A couple months ago I started reading The Bacchae—the story of the Greek God Dionysus’ return to Thebes, where he’ll punish the king for not honoring his divinity.

I came to a conclusion about what the story meant before I’d even read it, which was my first mistake. Then I journaled about it for days after finishing, trying to figure out what it meant and what there was to say about it. That was mistake number two, not the journaling part but the willfulness. The compulsion to nail it down and in such a short time! I’ll say more on it later.

In my November offerings, I wrote a bunch about the Garden of Eden story (The Lovers), which I keep coming back to. More specifically, the two trees in the garden: The tree of life and the tree of knowledge.

The basic plot line is that God creates the first humans and then tells them they can eat from any tree in the garden except the one of knowledge. But when a snake tells Eve she’ll be like God if she eats from that one, she can’t resist—which, I don’t blame her. They do get knowledge from eating the fruit, but the most notable change is that now they also have shame.

From the perspective of theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the tree of knowledge stands for the human tendency to seek “arbitrarily constructed knowledge” (words from Keith Meador and Joshua Knabb, see source list) as opposed to knowledge formed in the context of relationship. In his view, that relationship is one with God, but I think it can be interpreted more broadly.

Maybe the suggestion is that when knowledge comes through a context of relatedness—with one another but also with the winter berries, the red fox, the pines, and so on—it has a sacred quality to it, an essence that knowledge constructed without input from our surroundings does not (Eight of Swords).

In acceptance and commitment therapy, the pursuit of arbitrarily constructed knowledge is one of many reasons humans suffer. We carry old tales for too long without input from the current environment that we wind up living in accordance with some version of reality that’s distorted past recognition. We fuse with our stories, of course, and then take them so, super seriously. Thoughts become facts, and so on.

I think part of the reason we do this is that there’s something about a good, compelling, juicy story that just feels good in a way that a more accurate understanding of what’s happening—a prickly, contradictory, ambiguous thing—just doesn’t. A lot of us will take a wrong, smooth story over a right prickly one simply because the smooth one’s a lot easier to hold.

One example of the bias toward simple stories is that a lot of people believe without question that it’s bad to experience pain. It’s a very compelling legend old as time, in which sadness is the monster to be slain, and if you’re anxious, well then you must have taken a wrong turn somewhere. Our stories are not without consequence, obviously, they move us.

In this case, the effect may be that a second belief grows out of the first—not only is pain bad, but it should be avoided and ideally, eradicated altogether. This is what we do with things we don’t like. And if that’s not a story worth questioning, I don’t know what is. For starters because if it’s out with the pain, it’s out with the values, then too. Because pain and preciosity go hand in hand.

—

There’s a metaphor in acceptance and commitment therapy about a two-sided coin which is meant to show how the pursuit of values and discomfort are linked. Part and parcel of a meaningful human experience.

The belief that values and discomfort even can exist apart from one another makes it so we can’t see how all the elaborate attempts to avoid pain also hollow out the chest and collapse the shoulders, so that we become passive, yielding too much to the thoughts and feelings we assume we can’t manage.

Psychotherapist Jenna LeJeune has an exercise on her website that uses this metaphor. Basically, it goes like this: Bring to mind something you value and write it on an index card. Pick something you care about, but have had a hard time making moves toward.

LeJeune suggests taking the following questions into account as you do this: “Who do you really want to be [in that relationship/endeavor]? What are some descriptors of how you would like to be in that area of your life?”

Now flip the card over, and here’s where the pain goes. Make a note of some thoughts or feelings that either have come up in the past or may come up in the future when you start taking action toward the value.

Maybe you’ll learn something new about yourself here. Like are you terrified of making mistakes, or of not being good enough, of being judged, wrong, rejected? Welcome! There are a lot of us here in this.

In my experience, having a name for something can be a solid first step in realizing you’re not alone. And realizing you’re not alone can be the start of a trod out from hopelessness.

The last step is to carry the card around with you for a week or so. Take it out once a day or however often makes sense and just sit with the question, am I willing to take the pain with this value, or is it time to let it go?

Don’t be hasty here, give it time. Because what’s amazing about this is that you really do get to let it go if you realize it isn’t worth it, and it’s your choice!

—

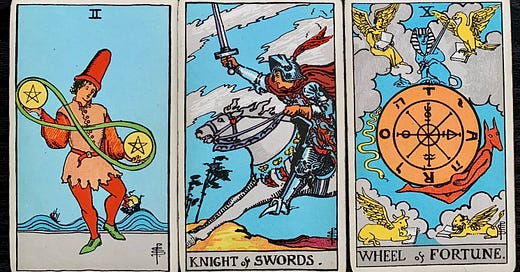

Another thing that happens with knowledge is that we assume it’s this fixed thing, and then strive to attain some ultimate version of it. As if some ultimate truth would save us from the processual work of being alive. (Knight of Swords)

In the Eden story, Eve eats the forbidden fruit because the snake tells her she’ll be like God if she does. That she’ll have wisdom, as if wisdom were a once-and-for-all kind of thing. I can really relate to this because I do get tired of not knowing. I’m driven every day by the hope of finding truth—even just one that could be Ultimate—so that I could get properly on with my life. Trust what I’m doing and be done with the doubts.

It’s so tempting, especially in times of great uncertainty, to see knowledge as a destination. To want to find that one truth that's a fit and put down roots there. It’s harder in a lot of ways to stay in the ambiguity of many truths at once, day after day after day.

Gray area needs something different from us than black or white do. A good, true-sounding story is something to hold on to and who among us doesn't want that? It feels good to figure something out, but it’s also fleeting. No sooner has the ecstasy of revelation kicked in than the stranger shows up with a new piece of information and says nope! Blows it all to hell.

The stranger’s arrival—which I’m using here to represent new data that doesn’t fit the existing story—can be really scary if you’d been hoping the work was over, as I know I have, many times. With the values example, it’s like having a story that because you’ve identified something precious, it’s automatically going to feel only good as you move toward it. And then as soon as the fear or doubt or anxiety kicks in—the stuff you didn’t plan for—you quit.

Moving toward something that really matters to you is often frightening. But where it gets really scary is when you refuse to accept the new stuff at all. Just get more and more defended against any possible contingencies, and more grafted with some calcified truth-tale. There are too many examples of this in and around me to go into here, but I’m sure you’ve got plenty of your own.

—

As I mentioned earlier, I finished reading The Bacchae this week, one of many myths about the Greek God Dionysus: half mortal, half God, raised by nymphs, first to make wine, and then followed around the world by a growing cult of wild women and animals.

Dionysus was worshiped all over the ancient world, in rites that I’m very early in learning about but that sound to have been centered around getting intoxicated and out from under the norms and social codes of society.

According to a Wikipedia entry on Dionysian mysteries, “Dionysus was the beast-god within, or the unconscious mind of modern psychology,” and that Dionysian rituals have been interpreted as “fertilizing, invigorating, cathartic, liberating and transformative…”

In the story, Dionysus returns to Thebes disguised as a stranger, planning to punish King Pentheus who has refused to honor Dionysus as a God. Long story short, the King will not bow to Dionysus—even after all the locals, including the blind wise seer Tiresias, and the king’s own mother, have converted.

Dionysus has a band of women who worship him through ecstatic song and dance in the forest. When he tricks the King into going to spy on the women during their rituals, the women spot the king and murder him. More specifically, the king’s own mother rips his arm off and his body is dismembered.

We find out later that she thinks she’s killing a lion. In fact, one of Dionysus’ powers is his ability to induce hallucination. And as if this weren’t bad enough, Dionysus then punishes the King’s family by turning them into serpents and banishing them from the land.

So, okay. I went into this story so excited to read about the arrival of a new God, kindness to the strange and mythic tellings of madness. It didn’t take long before I realized that Dionysus is really hard to sympathize with. He’s vengeful, arrogant, petty, ruthless, power-hungry and blood-thirsty. He induces a mother to kill her own son and still finds that to be insufficient punishment for the crime of, what was it again? Oh right, not worshipping him.

The storytellers that I love—amazing as they are at parsing meaning from stories—assert in their own ways that there’s an irreverence to “using” stories to reinforce and affirm what you already (think you) know.

Martin Shaw, for example, has said that if you think you know right away what a story means, you’re not letting it do it’s real work, which he describes as a sort of “open-heart surgery.”

James Hillman wrote of the image itself as iconoclast—a new god with the power to dismember old, crystalized beliefs, tear them limb-from-limb when they’re more loyal to the norm than it deserves. Hillman felt that to impose our pre-set meanings on images (as in stories, or tarot cards) is to zap the life from them, reduce them to propaganda for our own teachings (1977).

So of course the story of Dionysus didn’t behave as I wanted it to. It didn’t line up with my saccharine idea about the merits of welcoming strangers, or being hospitable to new gods who bring change when it’s needed. How could I possibly take such a clean angle with someone like Dionysus? He was a god in disguise, but also vicious, merciless and cruel. More a case for hostility to strangers and change than anything.

This is the most interesting thing about the story so far, for me. It’s both illuminated and refused to indulge my need for neat meanings. I hunt them like a dog, desperate, a hound after something to sink teeth in. I dream all night and day of a locked jaw, a sure thing, to the point that my entire life is organized around it. And while I’d certainly prefer to be someone who rejoices in the arrival of new gods, new data, new songs and new dances, it just isn’t the case.

Around this time last year I was working a lot with the story of Tuan MacCairill, one of the first people of Ireland who lived a series of lives as a man, boar, stag, salmon and ultimately man again, this time, a prince.

As a salmon, he was caught by a king. There in the net of his next life Tuan was unable to do anything but writhe. And though he was born again as a prince—a good deal, you could argue—the royal, limbed life was nothing compared to his old life as king of the river.

This is something I also see in the Dionysus story, that pushing back against the new is not always a mark of un-wisdom. New Gods arrive who are vicious, and cruel. Some things we lose we will never get over and never get back. Just the scent of it will draw blood all the days of our lives. Octavia Butler taught us to think of God as change, and that may be true. But I don’t think change or God move according to our arbitrarily constructed rules about what’s good and bad. (Wheel of Fortune)

Coming back to the symbols of the trees in the Garden of Eden, maybe eating from the tree of knowledge is coming to a situation (like a relationship, or a myth) and imposing meaning rather than looking with fresh eyes and gathering it. It would be me saying simply, The Bacchae is a story of hospitality for the strange and “respect for new moments”—because I want it to be and that fits my agenda.

Eating from the tree of life, on the other hand, might look like saying, okay, yes, this is a story about a new God. But it’s not here to soothe or anesthetize with the promise of certainty or any full-body allegiances. There’s no one true takeaway, but could I bring something home from that, still.

Something I think I'm realizing about neat stories is that they sure do feel good like cool marble but, to borrow words from Stephen Jenkinson, they tend not to hold up in the trenches.

Happy new year!

This is the free monthly offering. If you’d like to support the weekly offerings, click the “subscribe now” button below. If you enjoyed this offering, click share. <3

Sources

Euripedes. (1915). The Bacchae. Longmans, Green & Company.

Hillman, J. (1977). Re-visioning psychology. Harper & Row.

Knabb, J., & Meador, K. (2016). ACT for clergy and pastoral counselors: Using acceptance and commitment therapy to bridge psychological and spiritual care (E. Nieuwsma, J., Walser, R.D., & Hayes, S.C., Ed.). New Harbinger Publications.

LeJeune, J. (2021). Pain and values: Two sides of the same coin. Portland Psychotherapy. https://portlandpsychotherapy.com/2012/06/pain-and-values-two-sides-same-coin-0/

Von Franz, M. (1996). The interpretation of fairytales: Revised edition. Shambhala.

Thank you for your offering, I’m a new weekly subscriber and a massive fan of your book. I’ve gifted several copies to my friends! I’d like to know more about the story of Tuan MacCairill and read/hear your offerings from last year about it but can’t find them in the archive. It only goes back as far as July 2021. Thanks. ✨