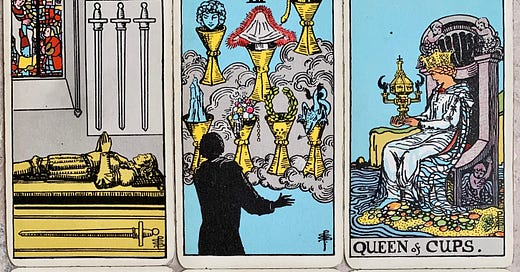

Image description: Six Tarot cards by Pamela Colman Smith from the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot. Left to right and top to bottom, they are Four of Swords, Seven of Cups, Queen of Cups, Ten of Wands, The Empress, Ten of Swords.

To listen to me read this offering aloud, click here.

I started my first journal when I was five in a plastic Minnie Mouse book with one of those little locks the diaries used to have. I first “wrote” in it by dictating highlights of the day to my mother, who’d print on the pink lines on my behalf.

That was also the year I began to piece my own words together in hardly legible, all capital letters. I still have bits from the journal, and in the scrawls from that year I can see the evolution of a small girl scratching her way toward privacy, autonomy, freedom. I think I pushed myself to learn to write because I sensed it needed to be done alone.

As I got older, writing was how I’d accommodate the bulging parts of my experience that were too big for my small body so that they could be seen and honored, with a name. Poems offered the strange pairing of warm interiority with the possibility of being known. Still today when the world feels prickly I take my stinging skin and turn to story.

I’m grateful to have words, and writing and there’s an escapist dimension to it (Four of Swords). I write for a living now, but I wrote as a child to make like I wasn’t holding things my hands were too small to carry.

We all do this as kids, in all kinds of ways, and there are ten thousand names for it. Creative adjustments, the start of a complex. For me it appears as a line in a Robert Bly poem called “One Source of Bad Information,” where Bly says there’s a child in all of us, “about three years old who hasn’t learned a thing for thirty thousand years.”

Having been given the inappropriate developmental task of saving us from death, Bly notes that the child tells us all sorts of things: “Stay home. Avoid elevators. Eat only elk.” That child’s gotten us through a lot, says Bly. “He’s got six big ideas. Five don’t work. Right now he’s repeating them to you.”

—

Robert Bly died last week, actually. My friend Charlie, who also died this year, introduced me to Bly when we first met after I’d told him I write about Tarot and psychology.

I almost always qualify my writing about tarot with “and psychology” to manage people’s perceptions of me. With people like Charlie, I’d say “behavioral psychology” since Charlie worked in behavioral health, loved science and I wanted him to know I meant business. But like many, Charlie heard the word Tarot and thought Carl Jung—thought ego and shadow and archetypes. Robert Bly was into Jung, too, and wrote a lot on the shadow.

Charlie had two small books he thought I’d like, which he handed over from his office shelf one day: Alice Miller’s Drama of the Gifted Child and Robert Bly’s A Little Book on the Human Shadow.

In the Little Book, Robert Bly writes about how to “eat the shadow,” that is, how to call back the parts of ourselves that we’ve thrown into the world unknowingly, as is the case when we’ve assigned someone else a feeling or story that actually belongs to us.

This is called projection (Seven of Cups).

In addition to that visual, I’ll also offer this: I trust my instincts but they tend to come with stories I’m less trustful of. Like if I sense an energetic shift then there is one, but that feeling sends out ten sharp-toothed hell hounds with vicious tales to tell. Soon they’re patrolling the block, latched onto a leg, assigning something I feel or believe to an unwitting participant, who you can hear in the distance crying, “I had nothing to do with this!”

Projection can look like feeling abandoned by someone when it’s been two thousand years since you remembered you had a body. It could be fearing a harsh critic when you wouldn’t touch grace with a flag pole. It might be feeling unwelcomed by others—and hurt by that—when you yourself want nothing but the sound of twigs under a boot. Nothing to shroud that tender crunch but the cawing of crows, the light pad of a fox paw on a dirt floor and your own interior, dreaming of God. In other words, what we don’t claim for ourselves we give out and assign to others. Or at least that’s how Bly talked about it.

Bly wrote that to retrieve our projections, we could use language. Something I’ve certainly done. He wrote that “certain kinds of language are nets, and we need to use the net actively, throwing it out. If we want our witch back, we write about her; if we want our spiritual guide back we write about the spiritual guide rather than passively experience the guide in another person.”

If you’re not a writer, Bly writes that "painting or sculpture may be right” and that “When we paint the witch with conscious intention, we soon find out whose house she’s in…[it] involves activity, imagination, hunting, asking.” (Queen of Cups)

—

The Queen of Cups’ deep listening brings me to another of Bly’s poems called “Things to Think,” where he describes a quality of receptivity where the listener imagines that the phone rings and the caller brings a message that’s the width, depth and weight of a boulder.

He writes, “think that someone may bring a bear to your door, maybe wounded and deranged; or think that a moose has risen out of the lake, and he’s carrying on his antlers a child of your own whom you’ve never seen.”

But my favorite part of the poem is the last stanza, where Bly writes:

“When someone knocks on the door, think that he’s about

To give you something large: tell you you’re forgiven,

Or that it’s not necessary to work all the time, or that it’s

Been decided that if you lay down no one will die.”

(Ten of Wands)

I’ve worked too much these last few years, and the compulsion to produce feels alive on its own accord in the pathways of my lungs and limbs. I love my work, and writing—for the most part—is therapeutic for me. But saddling myself with tasks so that I’m busy all the time is a coping strategy. Without a doubt.

Like most people I know, there is an archive of angst that only time has touched laying in the many locked rooms of the psyche that I think of as mine. The good news is the rooms require just one skeleton key to access. The bad news is the key is an elixir; of time, rest, and surplus energy. Ingredients that it seems so much in our modern world is designed to hunt and capture.

When I do slow down, there’s often a lot there waiting (Four of Cups). Cerebral, I seek for a story, a way to assign it. Symbols like words are good for this. A place to put life’s formless material—a sturdy top, bottom and sides. For me this generally leads to more writing. Which is good in many ways but not all, because writing is still work. It’s tricky.

I’ve been thinking about what I relinquish in the endless state of feeling like there’s more to do than will ever get done and that that’s unacceptable. It’s a weird sort of scarcity with insatiability, unworthiness and shame mixed in. When I keep busy I give up tending to what’s torn at the seams and tattered with neglect; a tending which is painful. Reckoning is painful. The more I put it off, the harder it gets.

In November I wrote all about shame in the weekly offerings. I explored knowledge and place and the Garden of Eden story. I wrote that shame involves a sense of being bad that stimulates withdrawal and creates separation.

It makes sense that the compulsion to do anything too much, like work, could be rooted in shame. Because when you move endlessly toward something, like work, you’re pulling away from something, too. More work means less winter walks, cold deep breaths, slow and true questions. It means I don't call my parents, I don’t mop the floors, I sit with one leg hanging off the side of the chair when I eat.

Keeping busy means I don’t care for things that need and deserve care, like my truck, which makes a weird sound when I turn to the left, but—you guessed it—I’ve just been so busy. Part of me’s scared I got swindled at the dealership in such a rush to leave Cali, as always, so I avoid it altogether. Shame.

In last week’s offering I shared a quote from Andy Fisher’s book Radical Ecopsychology which says that “in a violent society such as ours the discovery of a tremendous well of shame…is an event waiting to happen for most of us.” What I’m trying to say is, shame and rest feel related.

Of course, if your problem is that you work too much when you don’t need to, that’s privilege. The global exploitation of human labor negates the possibility of adequate rest for so many. And for those who can, I want to know why it’s so hard.

I want to know what would be needed to really accept it, if someone were to knock on the door and say it’s not necessary to work all the time. That no one will die if you lay down. That you don’t need to earn the presence of loved ones as if love is a wage paid for your undying and limitless service. What would it take to believe them if they were to say, “you are forgiven.”

All I have that remotely resembles an answer to these questions are the obvious. It’s the grief that makes rest hard. It's the unworthiness and the shame. It’s the internalized values of limitless growth and endless production. It’s the having been told through many lifetimes that we exist because of what we make or do or give the world. It’s capitalism, ableism, misogyny. All of this.

So I’m going to share some charms now—on rest—which may or may not be useful for you, if you, too, have these questions. These charms will be offerings to the questions themselves, which I hope will appease, or at least stimulate movement in some way.

—

1.

In The Disappearance of Rituals, philosopher Byung-Chul Han writes that rest is “an essential part of creation” and he cites The Old Testament’s Genesis, to prove it, and the existence of the Sabbath.

“[Sabbath] consecrates the work of creation. It is not mere idleness…Sabbath rest does not follow creation; it brings creation to completion. Without it, the creation would be incomplete. God does not rest on the seventh day simply to recover from the work he has done. Rather, rest is his nature. It completes the creation. It is the essence of the creation. Thus, when we subordinate rest to work, we ignore the divine.”

In this view, rest is what makes creative work sacred. (The Empress)

—

2.

In Robert Bly’s poem “Things to Think About,” he describes a quality of listening where you imagine that when the phone rings, the voice on the other line carries “a message larger than anything you’ve ever heard.”

Byung-Chul Han also writes that contemplative rest performs the radical task of allowing for silence, which gives rise to a “special receptivity” and a “deep, contemplative attentiveness.”

To adequately hear the voice at the door who says you’re forgiven, or the cry of your long lost child, Han says rest may nurture the capacity for deep listening.

—

3.

In the Rituals book, Han also talked a lot about a related concept of “communication without community.” The compulsion to be in constant connection—through social media, for example—seems a natural compensatory response to vast wells of unprocessed shame, which is itself so isolating.

But the urge to communicate constantly reduces our capacity for contemplation and maybe also for listening. Han writes, “[it] means that we can close neither our eyes nor our mouths. It desecrates life.” I think he’s saying that silence, contemplation and receptivity have a restorative power. Not exactly counterintuitive, it makes complete sense.

I’m noticing the use of the words consecrate and desecrate here.

Consecrate (as in “rest consecrates creation”) means to make something sacred.

Desecrate (as in constant communication desecrates life) means to “divest of sacred character.” I think of Pamela Colman Smith’s Ten of Swords here, which shows the diminishment of life by ten swords to the back, perhaps pointing to an excess of intellect and verbal communication.

—

I’ve been taking long walks to rest but will admit I make even that into work.

I snap pictures of flaming red maples and late autumn roses for my Instagram story without thinking.

I dream tweet-length thoughts about the red fox with a floating tail, turned blue by the moon.

Sometime over the last ten years events like these moved imperceptibly from something hallowed, to content for a public gaze.

A gaze sustained by the collective compulsion to check and a shared, addictive dopamine loop.

Thank you for being here, wondering with me.

This is the free monthly offering. I also make weekly offerings, which you can sign up to receive here for an exchange of $5 per month, $50 per year or more.

Sources

Bly, R. (2000). Eating the honey of words: New and selected poems. Harper Perennial.

Bly, R. (1998). Morning poems. Harper Perennial.

Bly, R. (1988). A little book on the human shadow. HarperOne.

Fisher, A. (2013). Radical ecopsychology: Psychology in the service of life (second edition). State University of New York Press.

Han, B. (2020). The disappearance of rituals. Polity.